From AFR Boss Magazine (by Alex Pollak)

Senior executives, big fund managers and asset consultants have a problem: they know that too much money is concentrated in too few companies. They have seen the effects of this in bad news stories like Woolworths, Myer and even Fairfax, the publisher of BOSS. They are fearful that it will ultimately hit the Australian banks. The problem is short-termism.

The question isn’t whether it exists (it does), or even why it is such a company-killer (it is) but why it is so embedded in corporations in Australia, and around the world, and how it will damage many investment portfolios in the coming years.

A comparison of the 2014 and the 1995 Fortune lists of the top 100 companies in the US reveals a startling fact: 44 of the names have vanished. The average lifespan of a US company has dropped from about 60 years in 1960 to less than 20 years. At the current churn rate, 75 per cent of the S&P 500 will be replaced by 2027. People now live longer than companies.*

There isn’t a definitive study on the Australian market about this yet but we won’t be immune.

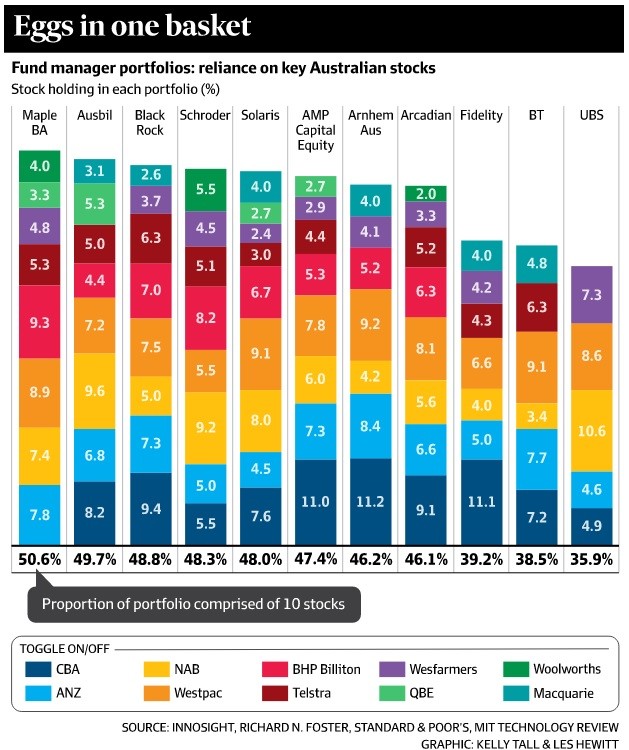

Large capitalisation managers index-hug the same 50 stocks.

The question executives and fund managers need to ask themselves is: do Australia’s corporations and institutional investors have the appropriate structures and mindset to prepare for the competitive impact of disruption?

This is no small query. Paul Keating set in motion the compulsory superannuation scheme, which is now up to $2 trillion. Superannuation is, as any Treasury official will tell you, mostly just a tax structure. You get a tax break on money to fund your retirement, which otherwise you wouldn’t have.

And Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull is now working to introduce some new tweaks to the system, which could provide the regulatory and tax frameworks that will push this further, and importantly, more towards innovation. But just how, far no one knows yet – and if the politics are too difficult, it could be that government fails in this. And that would set us up, in a negative sense, for decades to come.

PROBLEM WITH TWO PARTS

Understanding short-termism reveals it is a problem with two parts that lock together to create bad outcomes. One part is played by the investment industry itself – the managers and consultants – and the other by the big listed companies.

From the corporates’ side, investing for the long term is hard because management must ensure there is no slippage in profit and profit growth. If profit slips, the slipping company pays heavily in terms of a falling share price, which in turn affects management remuneration through the bonus and share schemes.

Simply put, executives don’t like to see their bonuses cut and will kick the problem down the road as far as they can, so it is the next executive’s issue. In a tough economic environment (in any economic environment) this means that risk-taking, pushing the company meaningfully down a different, disruptive track that may be critical to its long-term success – is too often simply off the agenda. It must be, because it cuts into short-term profit growth and the bête noire of the Australian investment landscape, franked dividends.

Franked dividend payments and short-termism go together like peas and carrots.

Franked dividend payments and short-termism go together like peas and carrots. In the US, where there is no dividend franking, companies do not provide significant dividends to shareholders, preferring to re-invest the cash that would otherwise be paid out, so generating a return on the return. However, in Australia, the pressure on the top 20 companies to pay a dividend makes re-investment in the kind of innovation that will disrupt their businesses in the near term and grow them down the track that much more difficult.

The second part of the problem is the investment management industry itself. Irrespective of whether the manager is BT, AMP, Colonial First State or a host of others, large capitalisation managers index-hug the same 50 stocks.

EXISTENTIAL ISSUE

Why does it work like this? Let’s say you are the portfolio manager of one of the big investment management companies in Australia and you have $15 billion to invest. The critical issue here is that this investment must not materially underperform the index. It is fine if it performs in line with the index, or even outperforms, since that makes you look better at investing than your competition and may help to get more investors, which is good for your business. It is also fine if the index goes down and your fund goes down in line with it, because it is a credible defence to cry ‘bear market’. But if your fund underperforms, even for periods as short as a year, then your investment management process will become the subject of scrutiny to determine whether or not you are competent. The business may even lose its rating and accreditation as a preferred manager.

This is an existential issue – if confidence in the investment process of the business is shaken, the fund loses investors. Lose enough investors and the business ceases being able to cover its costs and so could disappear. The incentives are clearly asymmetrical: there is no risk attached to investing at index weights, even if returns are negative, but it is a business-ending risk for a portfolio manager who attempts to outperform the index and fails. The wisdom of crowds determines that the money will be invested in line with the index. And thus it is that most funds look the same in terms of their holdings. This is what drives the index investment from the fund management perspective.

The incentives are clearly asymmetrical

Because the institutional funds, which make up about 70 per cent of the entire $1.5 trillion local sharemarket, are so heavily skewed toward the same companies, and at similar weights, there is incredible concentration risk in companies that are most heavily invested in not innovating. (This is clear in the alarming fact that our big four banks rank in the top 50 banks by value globally, despite being in an economy which represents only 2 per cent of the global GDP.) The focus is on the merest hint of any loss or weakness in this quarter’s profit numbers. The first casualty, then, is innovation, sacrificed to short-termism.

There are ramifications of this all the way up and down the capital allocation line. Investment in the Australian sharemarket by Australians has never been higher, but it has never been more dangerous to take an index bet. This is simply because disruption globally is laying waste to an unprecedented number of companies. As if to underscore this, the ATO regularly releases data showing the underinvestment by Australian self-managed super funds in offshore assets: less than $2 billion compared with $150 billion in Australian shares (according to the Self-managed Super Fund Statistical report for 2013).

We absolutely know that just around the bend – in banking, or retailing, or indeed transport – there is a whole world of change which will affect the traditional models and therefore the value, of many industries in Australia. Companies are paying lip service to disruption, but when it really matters, when it comes to investing real time and resources and money, it is absolutely off the table, because it cuts into short-term profit growth. The whole market is geared to the kind of short-termism that entirely excludes this kind of investment.

And all up and down the value spectrum, even small private concerns and start-ups, this creates capital shortages along with bottlenecks. Small-caps, and even mid-caps, are ultimately price takers when it comes to capital allocation, with the system stacked against them, unless they are the hot-as, earnings-free chosen in cloud computing, biotech or recruitment, which can trade at valuations of 100 times revenue.

LIQUIDITY A SERIOUS ISSUE

The lack of depth of the Australian market outside the top 50 stocks – and the fact that from number 28 down, these companies are capitalised at less than $10 billion – means that small-companies managers who actually make their living trying to get ahead of disruption, very quickly run out of companies to invest in. To explain: a small-companies manager with $10 billion to invest outside the top 50 companies would have more than 5 per cent of every company he chose (assuming a 30-stock portfolio, equal weighted). At this level, liquidity – meaning just being able to buy and sell without moving the price around by 10 per cent – is a serious issue.

This is the reason two of Australia’s most respected small-companies fund managers – Paradice Asset Management and Kosmos – reduced the size of their funds by handing back more than $1 billion to investors, effectively saying, “There are too few companies available for us to use your money to invest in.” But the bottlenecks even create problems for the select group at the very top. Too much money chasing too few investments results in companies getting priced for perfection, meaning they must hit impossible earnings hurdles just to maintain valuation, let alone increase. It’s all part of the bubble and drought nature of investment in Australia that is so dangerous for everyone: capital provider or company.

Too much money chasing too few investments results in companies getting priced for perfection.

Ironically, too much money chasing too few assets is the outworking of Keating’s genius in mandating a compulsory super system, which, curiously, at $2 trillion is now 30 per cent larger than the Australian sharemarket. But the fact that the money is there in the first place means there has been a measure of success. But just like business, success can’t stand still, it has to adapt.

These adaptations can take many forms. At the corporate level, tying a portion of management remuneration to longer term performance is one. There is no substitute for investor self-education, but some mandatory broadening of superannuation investment so that it includes offshore equities as part of a balanced approach would also help.

The government’s recent shifts in its significant investor visa criteria, where property and corporate purchases above a certain threshold by a foreigner now require investment in venture capital and small capitalisation companies (amounting to 40 per cent of the total investable sum) could also work. And of course, the current government is also pursuing tax breaks for investors in disruption.

Any or all of these may work, but all (and others) should be tried, before the enabling technologies that are collapsing value chains and business models really get down to their magic of destroying a generation of companies.

What will disrupt the disruptors?

27 Jun 2025E&P’s Words on Wealth Podcast interviews Alex Pollak and Raymond Tong on ‘AI’s Expanding Reach’

26 Jun 2025‘Beating the market in a time of hyper-disruption’: Alex Pollak features on EquityMates Basis Points

25 Jun 2025Cage fight: Trump v Musk! Alex Pollak features in SBS On the Money

15 Jun 2025Share this Post