First published BRW and Smart Investor, 14 August 2014 and written by Loftus Peak’s CEO Alex Pollak. Australian investors, especially self managed super funds, should consider diversifying their portfolios to include blue chip global disrupters like Tesla, and away from Big Oil.

Look, no gearbox – and not much gear at all. The simple chassis on Tesla’s electric vehicles poses a big threat to the complex supply chains of traditional car makers.

Now that China has effectively greenlit the electric car industry globally (new rules, to be phased in over two years, mean that not less than 30 per cent of all new cars bought for official use in China each year must be “new energy” vehicles), it seems like an apposite time to be talking about where the newest and by far the largest waves in disruption are heading: directly towards Big Oil and Big Auto.

The Stone Age didn’t finish for lack of stone.Sheikh Zaki YamaniRemember, as (of all people) former Saudi oil minister Sheikh Zaki Yamani once pointed out, “the Stone Age didn’t finish for lack of stone”.

The core to business disruption is the better mousetrap. The current mousetrap – expensive oil, environmental damage, 100 years of conflict through US/Middle Eastern geopolitics – is clearly broken. But the Chinese are not looking at solving the world’s problems. Like all good disrupters, they are just trying to build a better mousetrap – a cheap form of transport that does not pollute, something very close to their citizens’ hearts. As noted in the government’s release: Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, the Yangtze River Delta and the Pearl River Delta are places “where the task of bringing particulate matter under control is relatively heavy”.

Enter the electric car. Right now, it is hard to play on the long side, although there are some obvious places to start. For example, BYD (1211.HK), a Chinese battery company that Warren Buffett took a stake in four years ago and which jumped 4 per cent on the news. It is capped at $18.9 billion, and is trading on a price-earnings ratio of just under 80x. It will probably go up just because it’s closest to the pin, but it should be noted that less than 10 per cent of the company’s business is in electric cars right now. (Another is Syrah Resources, a graphite/vanadium for batteries play that Glencore has just bid for. Orocobre is aiming at lithium for batteries. All have jumped.)

The simpler, longer term and probably better trade would seem to be something around Big Oil and maybe even Big Auto. In the US, around 59 per cent of all oil consumed is in transportation. Remember, the nature of disruption in business is that it always starts small, normally with a few disgruntled punters speculating about how the world would look if only the technology was there to make it happen.

The Big Auto/Big Oil disruption could be ugly.The Big Auto/Big Oil disruption could be ugly, because the stakes are almost unimaginably high. There are tens of trillions of dollars tied up in them. This in no way should be viewed as a trivialisation of the incalculable human and environmental cost of a hundred years of oil realpolitik that is the Middle East today.

But setting this aside (if you can), it will become plain just how large the disruption will be when the industry groups start telling/yelling how long oil/auto has been here, and how long it will be here from now. Remember, they are paid (well) to say this. They always do this – check with Big Tobacco, or David Jones, Fairfax and Telstra for that matter.

It may seem easy to say that BMW is in the electric car space, as is Toyota, VW and Mercedes (among others) but the issues will be much deeper than this – analogous to saying that the traditional retailers can shift their business models on-line.

Simple threat

The photo of the Tesla chassis illustrating this piece is interesting for a number of reasons, none of them particularly to do with the batteries. Alert readers will note that the Tesla does away with almost the entire traditional motor mechanics of the car – meaning that it does not have a gearbox, clutch assembly, starter motor etc. Think about the Scalextric slot car – just motor and wheels. Now enlarge it. Presto, that’s Tesla. On top of the chassis sits only the passenger cabin itself.

The photo of the Tesla chassis illustrating this piece is interesting for a number of reasons, none of them particularly to do with the batteries. Alert readers will note that the Tesla does away with almost the entire traditional motor mechanics of the car – meaning that it does not have a gearbox, clutch assembly, starter motor etc. Think about the Scalextric slot car – just motor and wheels. Now enlarge it. Presto, that’s Tesla. On top of the chassis sits only the passenger cabin itself.

Big Auto, and all its suppliers globally, will need to deal with legacy plant and equipment which is on the books at values in the tens of billions – drive train assembly plants, automotive electronics, hydraulic and pneumatic systems, and cooling, to name just a few. How will traditional auto companies deal with this radical design rethink? Is it any wonder that Tesla is now capitalised at half the value of General Motors?

And Big Oil is, well, even bigger. The combined capitalisation of the four listed Big Oil companies (i.e. Exxon, Shell, BP and Chevron) is $US1200 billion ($1290 billion, or two-thirds the size of Australia’s entire superannuation savings), but this doesn’t tell the whole story, since those four represent only about 5 per cent of the total reserves, which are totally dominated by the big national oil companies such as Saudi Arabia’s Aramco, Iran’s NIOC and Russia’s Gazprom. The earnings multiples of the listed companies have been generally falling, even as the oil price has been rising – always the canary in the coalmine when discussing disruption.

The problem with electric cars isn’t storage.Looking out further, it is interesting to speculate on the most recent thinking behind the solar power/battery power vehicle question. The problem with solar has been that it is hard to store. The problem with electric cars isn’t storage – the batteries do that well – it’s that there aren’t enough charging stations. The solution that is emerging is elegant in the extreme – use the sun to charge the car during the day (between the drive to and from the workplace) and then discharge it into the home at night (leaving enough in the “tank” for contingency.) The numbers have already been crunched on this, and it can work.

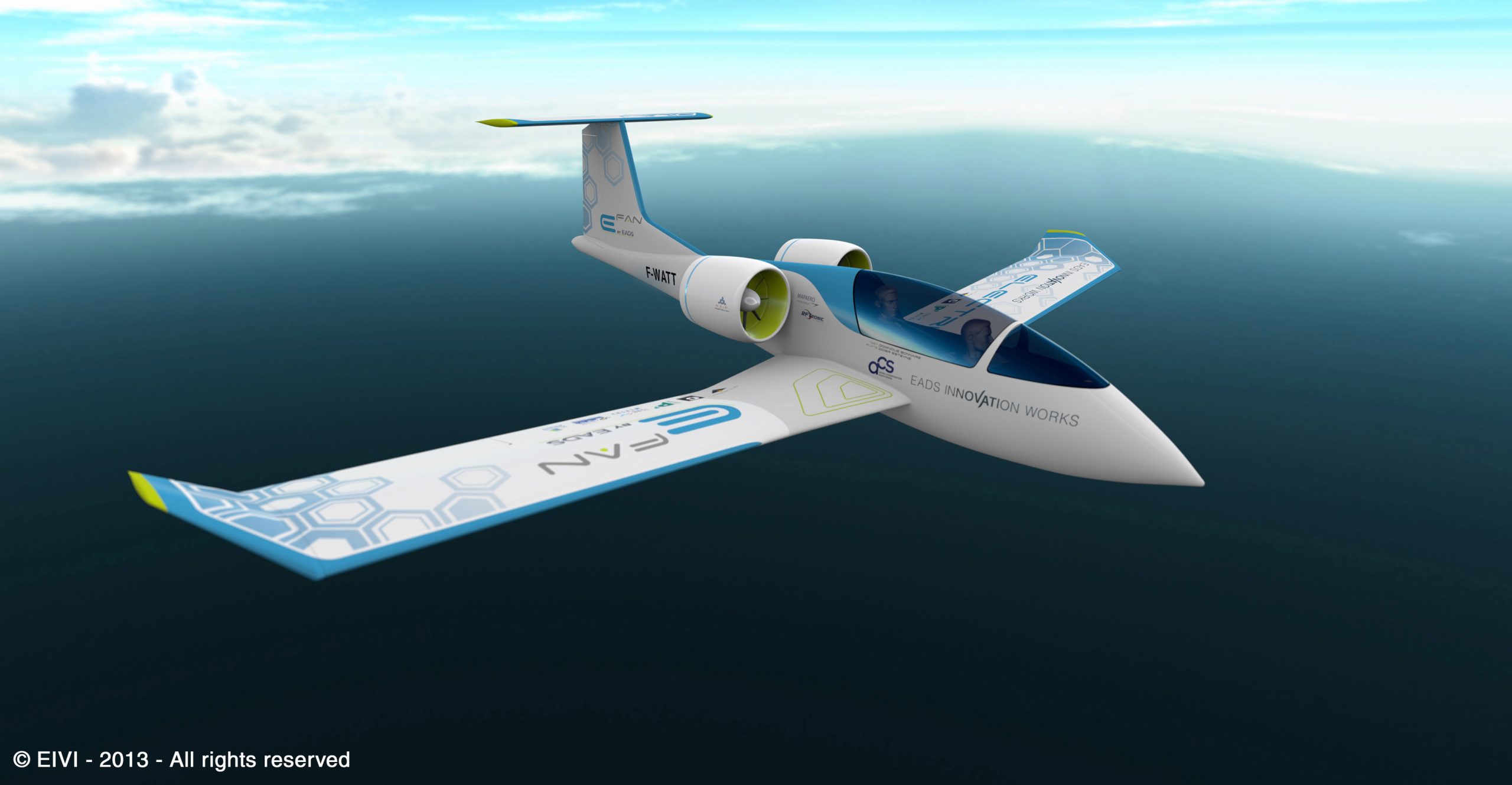

The E-Fan is a technology demonstrator of a fully electrically powered, all-composite general aviation training aircraft.© EADS Innovation Works

Expect much more on this in coming months. For example, Airbus has built and is trialling the first electric aircraft, the E-Fan. The two-seater was unveiled and made its first public flight demonstration at Bordeaux-Mérignac Airport in France, in April 2014.

Many of the most successful disrupters, in terms of business models, have chosen a simple business model and pursued it single-mindedly – find a segment of the market that is being poorly serviced both through the customer experience and the cost, grow your business from there, and then reverse integrate into the higher value chain. Let’s think about this in the context of power and transport.

- Untapped market? Globally, the push is on to reduce their environmental impact, so tick.

- Expensive? Cars, oil and power stations are expensive, and only getting more so. Tick.

- Antiquated cost structures that can be supplanted using the new technology – electric/solar is a better mousetrap. Tick.

- And: value of the new business could be very significant – in the trillions of dollars. Tick . . . tick . . . tick . . .

First published BRW and Smart Investor, 14 August 2014 and written by Loftus Peak’s CEO Alex Pollak. Australian investors, especially self managed super funds, should consider diversifying their portfolios to include blue chip global disrupters like Tesla, and away from Big Oil.

What will disrupt the disruptors?

27 Jun 2025E&P’s Words on Wealth Podcast interviews Alex Pollak and Raymond Tong on ‘AI’s Expanding Reach’

26 Jun 2025‘Beating the market in a time of hyper-disruption’: Alex Pollak features on EquityMates Basis Points

25 Jun 2025Cage fight: Trump v Musk! Alex Pollak features in SBS On the Money

15 Jun 2025Share this Post